Lots of year-end pieces this week. They are pretty consistent. Gloomy and doomy, various degrees of rage at various institutions, and surprisingly, a bit of a rainbow in the distance from a lot of them.

I don’t want to push back against the specifics or the specific characters so much as to offer up my own set of broad generalizations. So…

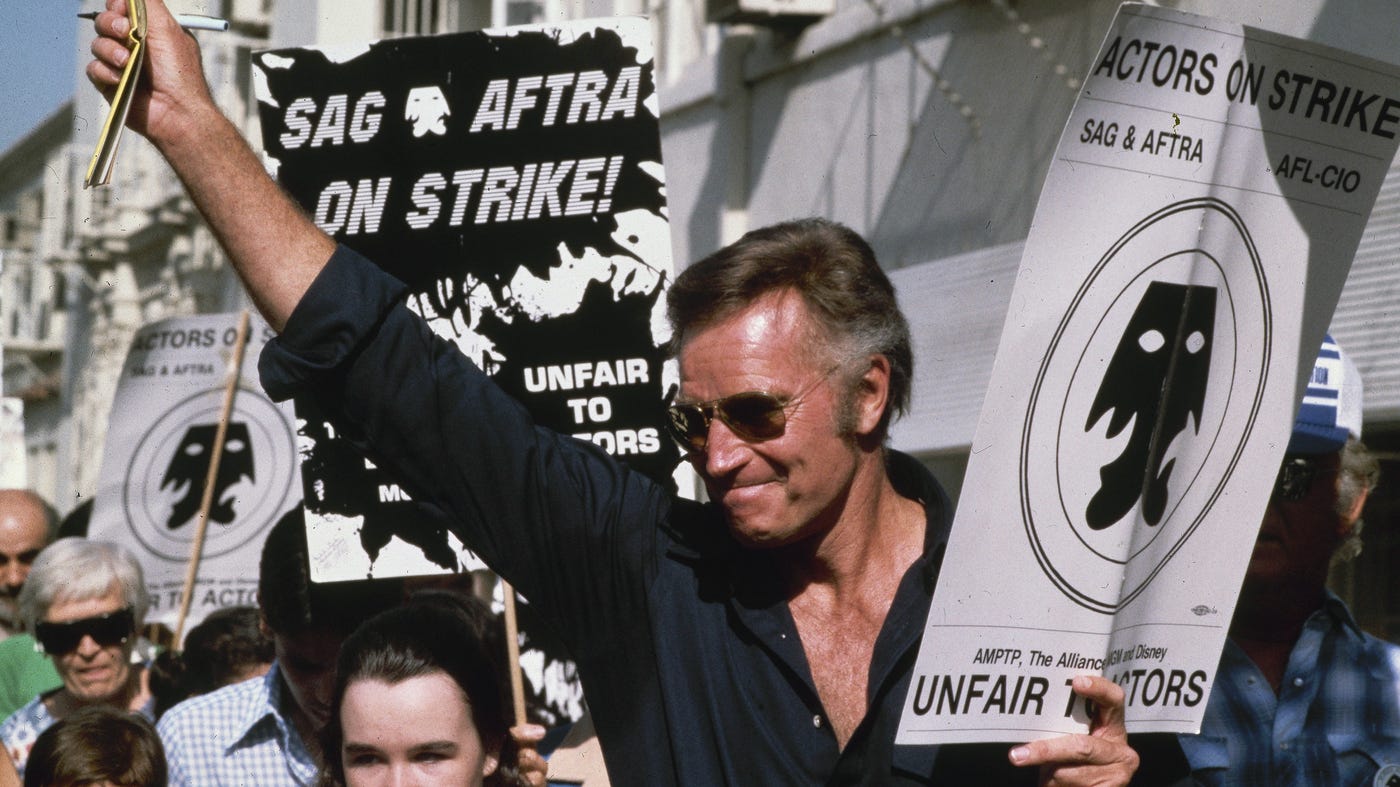

The strikes didn’t land on Plymouth Rock, Plymouth Rock landed on the strikes

Some people are really, really angry about the strikes and specifically, the unions. Sorry, but this is like blaming the teen babysitter because your husband (or wife) seduced her (or him).

AMPTP was the adult in this scenario. AMPTP is the one who sat out months of potential negotiations and then closed the deal with WGA in a week. They let SAG/Aftra sit and stew almost as long and, yes, that one took 3 weeks to close.

Why did AMPTP want a 5 month strike season?

My conjecture remains that they had already started the industry contraction and that the strikes gave them cover… cover that is now gone and leading to a ton of appropriate gloom and doom talk.

My number has been, for a couple of years, 30% on the content side. And by the end of the 5 strike months, I would say the studios were about a third to a half way through placing that kind of reduction in place.

This was going to happen regardless of the strikes or deals being cut just before strikes happened.

I’d love to be able to tell you that the industry would be in a better place overall without the strikes… to be able to blame either side for creating a more significant problem. As others have pointed out, there was no achievement in these strikes so revolutionary that everyone needed 5 months of pain.

There is no doubt that the short-term consequences make the shit sandwich even more bitter, especially in the next 9 months. But blaming the strikes for where things are is really missing the point and avoiding the fact that AMPTP made a choice.

Streaming is a television disruption, not a theatrical disruption

The movie model and the television model are not the same… they are not interchangeable… they are not whimsical.

Netflix’s streaming model has been, from the start, a third kind of model… also not directly interchangeable with the other models.

But the Streaming SVOD model is a direct infringement on the Legacy Television model, which has long been based on limited availability and advertising revenue from selling eyeballs to advertisers. The SVOD model says, I will gather content, old and new, and you will pay a monthly price to view it, on your schedule, to your taste, without boundaries of maturity ratings or even international boundaries.

In the Legacy model, each piece of content had a value, based on its ability to generate advertising, that was measured (conceptually) with every airing of every show.

In the SVOD model, the primary goal is to keep the bundle of content interesting enough to keep paying that monthly subscription.

Complicating this is that cable, for 4 decades, has charged consumers - almost all domestic households - to have access to a bundle of channels, sharing monthly revenues, and each of which was then monetized in its own way.

Netflix didn’t offer the “a’ la carte” dream to consumers. But for most, paying $80 - $180 a month for cable or satellite, the $10 offering from Netflix was an absolute and undeniable bargain in comparison, especially given that most people used/use about 20 or fewer of the 300+ channels they had/have available.

Once Legacy Media was dragged, kicking and screaming, into Streaming, they faced the immediate marketing problem of matching or trying to top Netflix, with a 7-year head start, instantly (or within a couple of years).

In Legacy Television, when a new network was trying to build an audience, they tended to go through various stages of building one segment of the audience, then another, then another, until it could try to service the whole nation. The idea of being whole from opening day was - and is - kinda insane. But that was the task that Legacy held itself to… competing with Netflix and trying to show off for Wall Street.

That’s when they dragged the movie model into this mess. Movies were bigger. Movies were more aggressively (and expensively) marketed. Movies weren’t structured to build an audience (as tv series do/did) so much as to explode out of the box and start deteriorating immediately, first in theatrical release and then through the windows after.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Hot Button by David Poland to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.