"Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to man.

For this he was chained to a rock and tortured for eternity."

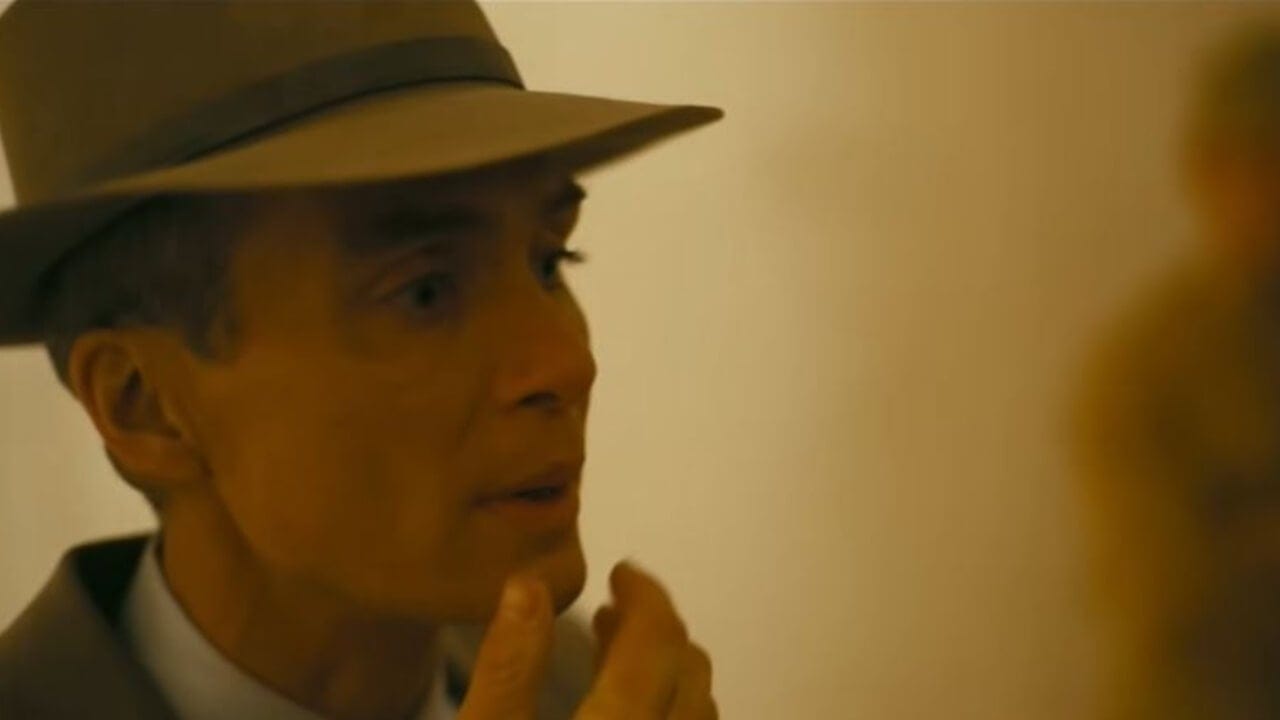

So begins Oppenheimer, the tale of fission and fusion. The first sentence of the quotation above, which opens the film, is the story of Oppenheimer and fission, the act of dividing or splitting something into two or more parts. The second sentence, which will be represented by Lewis Strauss (pronounced “straws”) is about the fusion that would torture Oppenheimer, mostly after the bomb, the result of the process of joining two or more things together to form a single entity.

Oppenheimer was a master of compartmentalization, splitting his life into many parts and managing to control them all. But with his decision to lead Los Alamos, the process he took on required the joining of many things together, most particularly Science and The Government.

I’ve seen the film 5 times now (in 4 formats) and I still don’t feel properly prepared to write about the work as it deserves… 10,000 words at minimum. Without the freedom to take deep notes - which I wasn’t going to do in full theaters - and really, the ability to work through the maze of the film with the ability to stop and process at times, it’s too much.

But I will do my best to offer some broad strokes. I don’t know if this really qualifies as a review, so much as a discussion of the work. I wouldn’t read further without having seen the film.

The color vs black & white thing has nothing at all to do with time. Oppenheimer’s perspective is in color. Strauss’ perspective is in black and white. I have confirmed that much in these 5 viewings. A few scenes cross over and are repeated from each perspective, most notably the scenes with Einstein. Oppenheimer is not in every color scene, but at least his imagination is the driving perspective in every one. Strauss was never in the various schools or Los Alamos, so there is no black & white in any of those segments, for instance.

Oppenheimer is Prometheus and Strauss is there to try to tie him to the rock for his perceived arrogance. But really, it is Oppenheimer’s own fears of what he has empowered that tortures him for the rest of his life.

It has struck me more and more, with each screening, how this film’s science vs government arguments are very reflective of what I would assume to be Nolan’s feelings about being a filmmaker and then having to hand his work to distributors to release it into the world as they see fit, more than he sees fit. Obviously, he has asserted all the power he has to control his films, demanding a long theatrical window, for instance, and to support the control that other filmmakers have of their films.

The camaraderie with which Oppenheimer and the other scientists work towards The Bomb, even with all kinds of in-house conflict, is, I imagine, how Nolan sees his work as an artist in the process of filmmaking, which can be dominated by one person (especially a writer/director/producer), but cannot be achieved by one person at anything like this kind of scale. You can lead, but you need a big village to follow and, at its best, add to your visions.

Obviously, a movie bomb doesn’t kill people like an atom bomb. But again, I would suggest that any artist, especially those who do have a large mainstream reach, considers the influence of their work on the world of filmic art… and sometimes, the world in whole.

But getting any movie made, much less a movie of massive scale, skill, and grace, requires some degree of myopia. Any multi-faceted discussion of Leni Riefenstahl may inspire fist fights, but it is unlikely that while making her films, she was thinking about how she was supporting the annihilation of millions of people. I am not saying that is a good excuse. But perspective matters.

In Oppenheimer, one of the most controversial moments, even for people who like the film a lot, is a bit of purely symbolic nudity and sex between Oppenheimer and Florence Pugh’s Jean Tatlock in the midst of the private hearing/prosecution over his security clearance. Some see it as random and unneeded, but it shows us how vulnerable he feels when he is forced to discuss his sex life, initially just stripped himself, and then in the imagined sex act with the dead women with whom he had one of the few relationships that seems to have really mattered to him. It’s also a critical moment in defining his relationship with his wife, Kitty, as he is aware that Tatlock haunts her too, as much as she has tried to stiff-upper-lip it.

Some ask why Jean Tatlock is showing more skin than Oppenheimer in the interrogation scene. I don’t think that Nolan or anyone else was really measuring for effect. For me, it is one of the most beautiful images I’ve ever seen on loss and regret and knowing how someone you love is being hurt by your actions while you have no power to escape the moment. Tatlock’s sex is very purposeful, in all 3 of their sex scenes. She seems to be getting something Kitty doesn’t get… and likely, doesn’t want. And Jean has no interest in the surface things that are part of what drives Kitty. The two women, confronting each other in words and imagination, are Oppenheimer’s ying and yang.

As long I am digressing to discussing the great moments of the film, another segment on Oppenheimer’s fear and regret comes in a Los Alamos celebration rally.

But first… the transition that comes right before it.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Hot Button by David Poland to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.